Basics & Beyond: New Kalanchoe For Cultivation

Kalanchoe blossfeldiana is one of the most popular potted flowering plants in greenhouse crop production. There are several reasons that contribute to the popularity of kalanchoes. First, succulent stem-tip cuttings of kalanchoe are relatively easy to propagate. Programming and scheduling flowering are also straight-forward. Kalanchoes are short-day plants and flower when the day length is equal to or less than 12 hours. Finally, the postharvest performance of kalanchoes indoors is excellent, providing long-lasting flowering and color in homes.

[blackoutgallery id=”64513″]

A few other species of Kalanchoe are grown in containers, for foliage and not flowers. Kalanchoe thyrsiflora, or flapjacks, is grown for its large, colorful leaves and coarse texture for use in landscapes and containers, while K. behariensis and K. tomentosa are grown as houseplants.

While only a few species of kalanchoe are grown commercially, there are 139 species in the genus. A number of other species are underutilized commercially as potted plants (Figure 1). This is due to diverse foliage, plant habits and, most importantly for flowering potted plants, unique flowers and inflorescences. However, there is a lack of information about how to successfully grow these species. We identified how to produce compact, flowering plants of selected Kalanchoe species with potential as flowering potted plants.

Programming Flowering

Research has found that several kalanchoe species, including the popular K. blossfeldiana, flower in response to day length, classifying these plants as photoperiodic, with respect to flowering. There are two types of photoperiodic flowering responses that have been observed in kalanchoe species: plants that flower after being exposed to short days (SD, short-day plants) and plants that flower after being exposed to a specific sequence of long-days (LD) followed by SD (long-short day plants). We thought that either SD or LD followed by SD may cause flowering in some of the species with commercial prospects.

We grew 20 different species of Kalanchoe under one of four photoperiod treatments:

1. Short-days (SD) for 16 weeks

2. Night-interruption (NI) for 16 weeks

3. SD for eight weeks, followed by LD for 8 weeks

4. LD for eight weeks, followed by SD for eight weeks

Nine species did not flower under any treatment. Furthermore, K. laetivirens, K. pumila and K. rosei had minimal flowering. Alternatively, K. glaucescens, K. laciniata, K. manginii, K. millotii, K. nyikae, K. rotundifolia, K. uniflora and K. velutina flowered when grown under SD for eight or 16 weeks. Since node number below the flower and days to flower for these species increased when NI preceded SD, and none of these plants flowered when grown under only NI, the NI inhibited flower induction. Based on these results, we classified K. glaucescens, K. laciniata, K. manginii, K. millotii, K. nyikae, K. rotundifolia, K. uniflora and K. velutina as obligate SD plants.

Once we identified that flowering could be induced under SD, we wanted to get a better understanding of the SD requirements for flowering. The critical photoperiod or critical daylength is the photoperiod at or below which flowering is induced for SD plants and this varies across different genera and species.

For some plants, 14 hours can be considered a short day, while for other plants, 11 or 12 hours may be considered a short day.

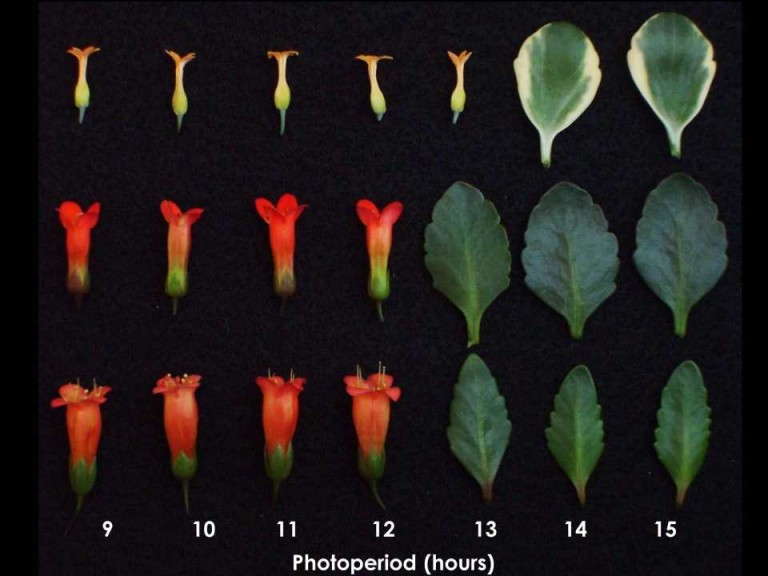

We grew K. glaucescens, K. manginii and K. uniflora under day lengths ranging from of nine to 15 hours long. We found that daylengths 13 hours and shorter induced flowering of K. glaucescens, whereas daylengths 12 hours and shorter induced flowering of K. manginii and K. uniflora (Figure 2). To keep plants vegetative, daylengths should be longer than 12 or 13 hours (depending on the species), though NI lighting is also effective.

In addition to identifying the critical photoperiod that induces flowering, we wanted to identify how long the plants needed to be under SD to induce flowering — the critical cycle number. Kalanchoe glaucescens, K. manginii and K. uniflora were grown under inductive SD anywhere from zero to eight weeks and then transferred to a non-inductive environment with NI lighting.

We observed some interesting variation across the species (Figure 3). K. glaucescens was completely induced to flower after only one week of SD, while K. uniflora required six weeks of SD to become fully induced. K. manginii was induced to flower after three or more weeks of SD.

Improving Quality

Many flowering potted plants are produced in fall, winter and early spring when natural light levels are low. However, the use of supplemental lighting during these times can improve the quality of crops. We wanted to identify how the daily light integral (DLI) affected the growth and flowering of select Kalanchoe species. K. glaucescens, K. laciniata, K. manginii, K. nyikae, K. rotundifolia and K. velutina were grown under an eight-hour photoperiod with a DLI of approximately 4, 9 or 17 mol•m-2•d-1.

For all of the species studied, increasing the DLI increased both the shoot weight and number of flowers, resulting in a higher-quality plant. Achieving a DLI of 17 mol•m-2•d-1 could be challenging in a greenhouse during the winter months; however, use of modest supplemental lighting to increase the DLI to 8 or 9 mol•m-2•d-1 will improve the quality of kalanchoe species.

Controlling Growth

In addition to managing the photoperiod for programming flowering and DLI for enhancing quality, controlling plant size is another important factor in containerized ornamental plant production. We applied foliar sprays containing water, ancymidol (15 ppm to 60 ppm), benzyladenine (75 ppm to 300 ppm), chlormequat chloride (750 ppm to 3000 ppm), daminozide (1250 ppm to 5000 ppm), ethephon (250 ppm to 1000 ppm), paclobutrazol (10 ppm to 40 ppm) or uniconazole (5 ppm to 20 ppm) to 11 different kalanchoe species two weeks after plants were pinched.

Although some chemicals performed better than others for different species, paclobutrazol and uniconazole were the most effective chemicals for reducing stem elongation across all of our species. Similarly, both benzyladenine and ethephon increased the number of branches.

Since the amount of growth regulation for a crop depends on several factors including container size and number of cuttings per pot, growers should experiment with a few different rates to find out what is best for the Kalanchoe species they are growing.

What Next?

Kalanchoe has some species with great qualities that could be used for flowering potted plants. While these species may not be widely available commercially, they may warrant some trialing in your greenhouse. The information we present here should be used as an aid to adopting some new and unique plant material in your flowering potted plant program.