How Banker Plants Can Help Growers Manage Thrips in Roses

Chilli thrips are a nuisance to rose growers, as their feeding causes foliar and flower damage. For the first time, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) researchers investigated the utility of a banker plant system for managing chilli thrips on roses. Recently published research in the Journal of Applied Entomology demonstrates the potential of this system for helping rose growers using two predatory mite species.

The Osborne Lab at the UF/IFAS Mid-Florida Research and Education Center in Apopka, FL, has researched banker plant systems for more than a decade. In the case of chilli thrips, the overall concept is that the pepper banker plants provide resources, food, and shelter, which are required by the mite predators of the chilli thrips.

In the case of roses, this plant doesn’t appear to provide suitable pollen or habitats for the predatory mites that are found to be effective in managing chilli thrips on other crops. The banker plant is placed in the greenhouse to act as a shelter for the predator to live and reproduce on. As the predator population increases, they will begin to move off the banker plant to feed on pests living on the other greenhouse plants.

Researchers frequently work to play matchmaker between host plant, predator, and pest. Finding the right combination helps growers control pests long-term and reduce pesticide use.

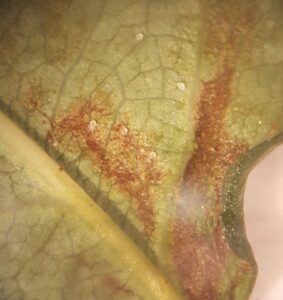

In this case, researchers wanted to know if they could establish predatory mite populations of Amblyseius swirskii and Amblydromalus limonicus using the banker plant concept to control chilli thrips on roses, specifically Double Knock Out roses, the most widely sold rose in North America and a major Florida crop susceptible to chilli thrips. Feeding by chilli thrips on roses causes visible damage, which greatly reduces their aesthetic value and can make them unmarketable.

“We get a lot of calls from rosarians that cannot find good management for chilli thrips and roses,” says Erich Schoeller, UF/IFAS postdoctoral researcher. “There are chemical options, but the growers want biological control options. Typically, most of the biological control options have a lot of issues with roses so we have not had a solution.”

“I have seen thrips destroy rose blooms in public gardens as well as personal rose gardens,” says Diane Sommers, President of the American Rose Society. “When this happens, it discourages people from growing roses, even while the availability of hardy disease resistant varieties continues to grow. In a recent webinar on how to use beneficial insects in the rose garden, the most frequently asked question was how to control chilli thrips.”

Predatory mites like A. swirskii typically do not establish well on roses due to the structure of the plant. Rose leaves are smooth and lack protective structures underneath that mites need for shelter and reproduction. But when pepper plants are added as a home for the mite predators, thrips damage to the roses significantly decreased.

“While we knew A. swirskii was an effective predator of chilli thrips on other crops, it was nice to show that A. limonicus was another effective chilli thrips predator,” Schoeller says. “A. limonicus had never been tested before on chilli thrips, so that was an exciting finding.”

Despite both mite predators controlling chilli thrips equally well, A. limonicus may offer a superior pest management solution for rose growers. A. limonicus is proven to manage other rose pests and moved from the banker plants to the roses faster than their counterpart A. swirskii.

Overall, both A. limonicus and A. swirskii are promising biological control agents of chilli thrips on Double Knock Out roses.

“In the future, we would like to run additional experiments to understand the minimum ratio of banker plants to roses you need to see the same level of control we did in our experiment,” Schoeller says. “We’d also like to test using both predators at the same time. But that’s down the road.”

This research was a collaboration between UF/IFAS entomologist Lance Osborne and USDA research entomologist Cindy McKenzie, and was funded by grants from the Floriculture and Nursery Research Initiative, USDA, and the Farm Bill.