How to Fertilize Woodland Wildflowers for Container Production

Native plants are increasingly popular with consumers, and with that demand, more native species are being grown in containers and forced like traditional perennials. However, when commercial producers work with native plants that are relatively new to cultivation, production guidelines are often limited or unavailable, making efficient production more challenging.

Why Fertilization Can Be Tricky for Woodland Wildflowers

Figure 1. Woodland wildflowers are commonly propagated vegetatively through underground storage organs, such as the scaly bulbs and rhizomes used in this study. | Iowa State University

Previous research we published in Greenhouse Grower® Magazine (April 2023) focused on fertilizing native prairie perennials grown from seed. Woodland wildflowers, however, are a completely different category of herbaceous North American natives. They’re prized for their early spring emergence, delicate blooms, and — for many species — an ephemeral growth habit, with shoots naturally dying back by midsummer.

Unlike prairie perennials, woodland wildflowers are not propagated from seed for commercial production. Instead, these species are vegetatively propagated using rhizomes, scaly bulbs, or crown divisions. each bringing unique nutrient-storage characteristics that may affect greenhouse performance.

Despite their popularity with consumers, basic production guidelines, especially fertilization requirements, are still unclear for many woodland species. This knowledge gap led us to conduct a study evaluating how fertilizer form (water-soluble vs. controlled-release) and fertilizer concentration affect the growth and development of container-grown woodland wildflowers.

How the Study Was Designed

Our experiment evaluated three concentrations of water-soluble fertilizer (WSF) and three different concentrations of controlled-release fertilizer (CRF) compared to unfertilized control plants to see how fertilizer form and rate affected finished plant quality in six woodland wildflower species.

We worked with:

- Great white trillium (Trillium grandiflorum) — rhizomes

- Wood poppy (Stylophorum diphyllum) — rhizomes

- Wild geranium (Geranium maculatum) — rhizomes

- Wild ginger (Asarum canadensis) — rhizomes

- Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) — rhizomes

- Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria) — scaly bulbs

All plant material was sourced from Warren County Nursery (McMinnville, TN; Figure 1) and stored for three days at 41°F in a cooler upon arrival.

Containers and Substrate

Plants were transplanted into 4.5-inch square containers filled with a soilless mix of coarse-ground Canadian sphagnum peat moss and coarse perlite. The substrate was amended with limestone to adjust pH and a wetting agent to improve wettability.

For the CRF treatments, fertilizer was incorporated into the substrate individually for each container prior to planting to ensure the correct amount was provided to plants at concentrations of:

- 1.25 lb/yd³

- 2.5lb/yd³

- 5.0 lb/yd3lb/yd³

For unfertilized controls and WSF treatments, plants were potted into substrate with no fertilizer incorporated.

Fertilizer Treatments:

- Control + CRF plants: Irrigated with clear, tempered municipal water throughout the study.

- WSF plants: Fertigated at every irrigation with 50, 100, or 200 ppm N from 15-5-15 (J.R. Peters), beginning at watering-in.

Greenhouse Environment

Greenhouse conditions remained constant throughout the study. The day and night temperature setpoints were set at 68°F for the 16-hour day period and 58°F for the eight-hour night period. Ambient sunlight was supplemented with high-pressure sodium lamps to maintain a daily target light integral of 12 mol·m–2·d–1 and a 16-hour photoperiod.

Six weeks after planting, when plants had reached a marketable size, we collected data on substrate pH and EC, plant height and width, and shoot dry weight. Dried shoots were then submitted to a commercial lab for tissue nutrient analyses to quantify macro- and micronutrient concentrations.

What We Observed

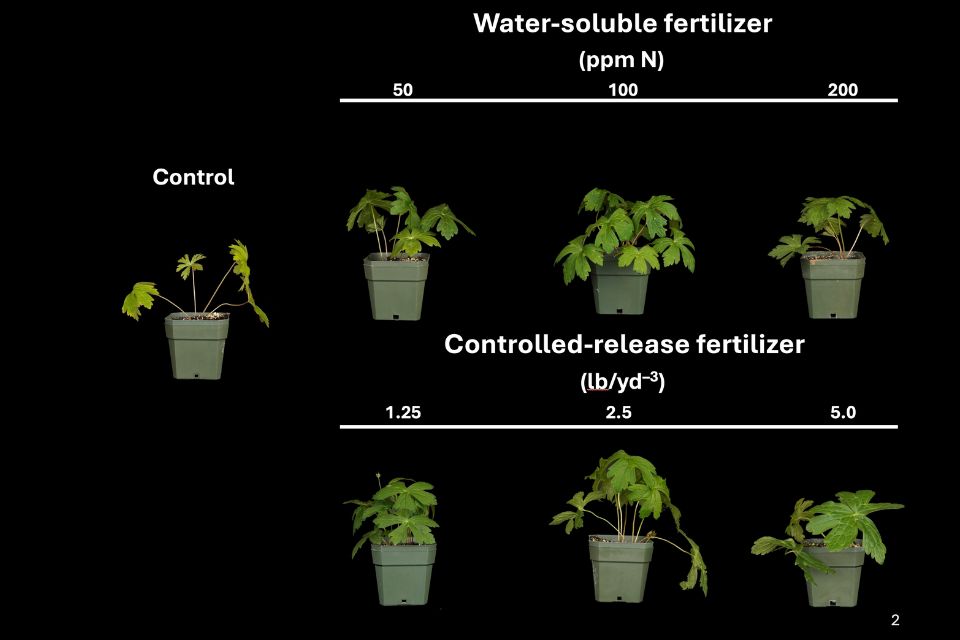

Figure 2. Wild ginger (Geranium maculatum) plants grown with no fertilizer (control) or provided with 50, 100, or 200 ppm N from water-soluble fertilizer or 1.25, 2.5, or 5.0 lb/yd3 CRF. Photos were taken six weeks after starting the experiment. | Iowa State University

Not all crops started equally well in the greenhouse. Dutchman’s breeches never emerged after the scaly bulbs were transplanted into containers. Great white trillium did emerge, but the emergence rate was so uneven that we chose not to include it in our final dataset. In contrast, wild geranium, wild ginger, wood poppy, and mayapple all emerged and grew in a uniform and typical manner.

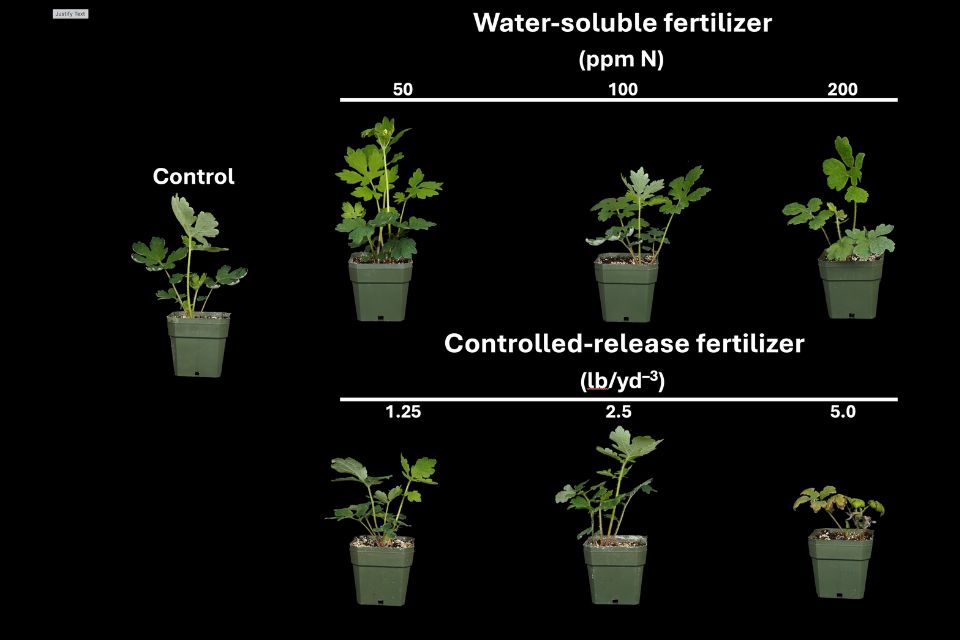

Adding fertilizer, whether WSF or CRF, and increasing fertilizer concentrations raised substrate EC compared to unfertilized plants for all four species. The opposite trend occurred with pH; as WSF or CRF concentration increased, substrate pH decreased compared to unfertilized plants. This pH reduction was more pronounced in mayapple and wood poppy than in wild geranium and wild ginger.

Plant size responses were modest. Height was similar across all fertilizer treatments for each species. Plant width for wild geranium (Figure 1), mayapple, and wood poppy were also unaffected by fertilizer, whereas wild ginger plants provided with either CRF or WSF were slightly wider than unfertilized plants. Shoot dry weights were comparable across all treatments for all species. However, wood poppies grown with the highest CRF rate (5.0 lb/yd3) showed visible foliage damage, including necrotic margins (Figure 3).

Supplying either WSF or CRF increased macronutrient tissue concentrations compared to unfertilized plants, but for most macronutrients, this increase was modest and did not show a strong dose–response trend as fertilizer concentration increased. Micronutrient concentration also rose in wild geranium and mayapple with WSF or CRF, while micronutrient concentration levels in wild ginger and wood poppy remained relatively stable across fertilizer treatments.

Interpreting the Results

Figure 3. Wood poppy (Stylophorum diphyllum) plants grown with no fertilizer (control) or provided with 50, 100, or 200 ppm N from water-soluble fertilizer or 1.25, 2.5, or 5.0 lb/yd3 CRF. Photos were taken six weeks after starting the experiment. | Iowa State University

When we look at all our responses together — plant growth, tissue nutrient concentrations, and chemical properties of the rootzone — we can conclude that the fertilizer needs of wood poppy, wild geranium, wild ginger, and mayapple during forcing are not high. Plant growth, as reflected by height, width, and shoot dry mass, was sufficient across fertilizer types and concentrations. In many cases, plants receiving the lowest concentrations of WSF or CRF were as well developed (or better) than those receiving the highest fertilizer rates.

Tissue nutrient data tells a similar story. There were no large differences in tissue nutrient concentrations across fertilizer treatments, further suggesting these species are relatively nutrient-efficient under the production conditions we tested.

Why might this be? The fertilizer was clearly available (evidenced by increasing EC and decreasing pH associated with higher WSF and CRF rates), so lack of fertilizer supply is not the explanation. Instead, we suspect these species relied partly on nutrients stored in their rhizomes and other underground organs to support the relatively rapid period of shoot development.

Ecologically, this makes sense. The woodland species in this study are some of the first to emerge in spring, quickly growing and storing energy before the tree canopy closes. Having stored nutrient reserves to fuel that early flush of growth may explain the nutrient-efficient response we observed in this forcing study.

Take-Home Message for Growers

Woodland wildflowers are endearing native plants with charm that sets them apart from more traditional perennials. Forcing these ephemeral species in greenhouse containers presents a strong opportunity to meet growing consumer interest in native plants.

While many production specifics for these species are still being refined, our results indicate that their fertilizer needs are modest. Providing 50 to 100 ppm N from a water-soluble fertilizer or 1.25 to 2.5 lb/yd3 controlled-release fertilizer is sufficient to produce appropriately sized, healthy containerized plants. Higher rates offer little or no benefit and, in some cases, may even reduce plant quality.

For growers looking to add woodland wildflowers to their spring lineup, these low-input fertilization strategies offer an efficient and reliable starting point.