ToBRFV: A New Tomato Virus in Town

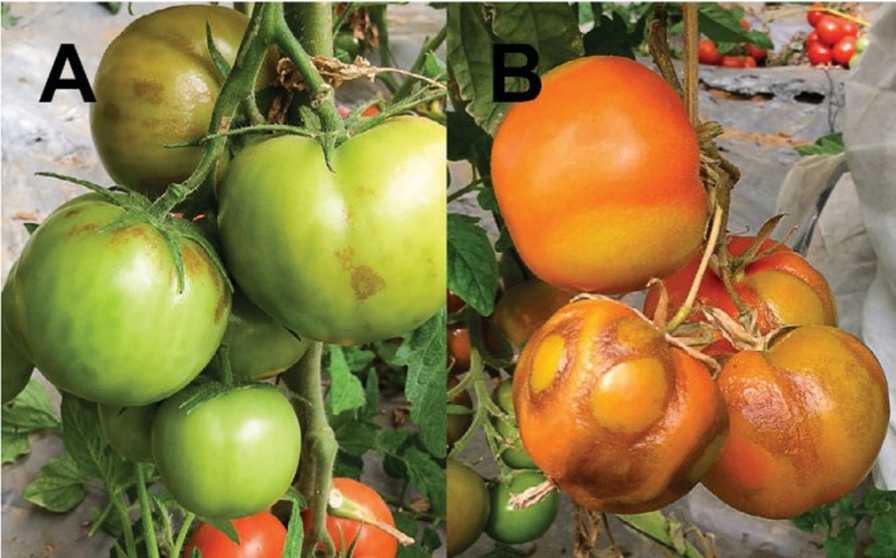

Symptoms of the ToBRFV on tomato fruit include blotched with brown necrotic spots leading to complete fruit abortion.

Photo courtesy of Seminis

Greenhouse tomato growers are being introduced to a new species of tobamovirus viruses that people have worked on for over a century — and something is different with this one.

“The tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) is a new type of the older well-known class of viruses, a different species with different biological properties because it breaks resistance and spreads rapidly,” according to virologists.

Starting about five years ago with its discovery in the Middle East, ToBRFV has spread to countries around the world where tomato production is conducted more in protected structures and less in open-field, although nothing is yet sacrosanct as the European Plant Protection Organization reported the possibility that bumblebees could carry and transmitted the virus to healthy tomato plants during pollination.

U.S. Border Crossings Detected

By 2018, the highly virulent virus was all over production fields in Mexico, affecting solanaceous crops, but especially tomatoes and peppers. From America’s southern border, it was a short journey across the international line with discoveries made in both Arizona and California in 2019. In Arizona, the virus targeted NatureSweet, producers of 18 million square feet under-glass plants annually on a combined 600-plus hectares on both sides of the border.

“We spotted it in one greenhouse in March of this year,” says General Manager Alexandro Briones Sanchez. “It was immediately removed and burned.”

Another incident occurred in a Santa Barbara County, CA, production greenhouse last fall and a market in Sacramento in August of this year that obtained its fruit from Baja, Mexico.

Don’t Place Your Hopes in Genetic Resistance, Yet

“The rapidly spreading virus represents a major concern for tomato production worldwide,” according to a report prepared by the California Tomato Research Institute in conjunction with the University of California, Davis Plant Pathology Department. It has already received an “A” pest-rating profile from the California Department of Food and Agriculture with the notation that “Because of suitable hosts and climate, it is likely ToBRFV can establish a widespread distribution in California wherever tomato and pepper plants are cultivated [and] crop production and quality of consumable fruit can be affected significantly [thereby] impacting their market value.”

Bob Gilbertson is a virologist and seed pathologist at UC Davis who recommends that because of its speed of spread, without assistance from any insect vectors, there should be a motivation for preventative measures.

“Reliance on genetic resistance doesn’t work as ToBRFV either doesn’t recognize or breaks down any resistance gene and can survive for long periods (up to 20 years) in soil, dried leaf tissue, or on contaminated tools and equipment,” he says.

Bayer Group’s Seminis Vegetable Seeds company reported the virus as “very stable outside its plant host, surviving on trellis wires, stakes, and seedling trays” and noting spreading might be possible through transplanting, pruning, staking, trellising, tying, spraying, and/or harvesting.”

The American Seed Trade Association (ASTA), says the new tobamovirus “has the ability to overcome all known genetic resistances, including the Tm-2 2 gene, which distinguishes it from Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) and Tomato Mosaic Virus (ToMV). Although similar to other tobamoviruses, ToBRFV is very stable and very infectious.”

How to Identify ToBRFV

Symptoms of ToBRFV are akin to those of TMV and ToMV involving leaves, fruit calyx, and the fruit itself. Generally, foliar symptoms include chlorosis, and infected plants will be stunted with leaves showing some degree of distortion and mosaic or mottle. ASTA researchers say there will be a distinct browning on the veins or tips of the calyx while fruit coloration will be blotched with brown necrotic spots leading to complete fruit abortion.

Once a suspect occurrence is discovered, something like a TMV Agdia immunostrip can provide a quick field-test prescreen, but quick remedial action like isolating the suspected plant(s) is recommended as a laboratory plant test might take 48 to 72 hours and allow the virus to expand and expose further.

No Need for Alarm, the Threat is Controllable

Remove the symptomatic plants and incinerate them while limiting access to and treating each infected greenhouse as a separate unit.

Gilbertson, who runs a rapid-detection ToBRFV laboratory at UC Davis, suggests early preventives are the smartest way to go.

“The virus isn’t a great seedborne pathogen, but it’s adequate enough to get around long distances,” he says, advocating a three-step process of before, during, and after planting.

“When you get your seeds, make sure they’ve been tested and found virus-free,” he says. “As an added safety, you can treat the seed with TSP (triple sodium phosphate), a detergent with a high pH that disrupts virus particles on the outside of the seed. If you do a 10% TSP treatment for an hour, you can virtually eradicate the virus from the seed.”

During the growing season, Gilbertson advises walking your greenhouse with the same intensity a chicken farmer does looking for predators on his flock.

“Look at every row for some sort of mosaic, a mottle in the leaves or leaves that are elongated like a shoestring,” he says. “If you find some, it’s time for roguing, removing infected plants quickly to minimize the amount of inoculum.”

Because transmission is by contact, especially in greenhouses where plants are more frequently handled, extreme sanitation is called for. Workers need to glove up and wear protective clothing, constantly washing their hands in soap and dipping their tools in TSP or a non-fat, dry-milk protein solution.

After the growing season, take everything down and spray the inside of the house as well as all the benches, tools, and strings. A new crop should get a new beginning without fear of any previous contamination.

“Protected culture tomato growers have to practice this type of sanitation for bacterial canker, another serious potential disease requiring strict cleanliness, so this type of sanitation effort isn’t a foreign concept,” Gilbertson says. “Granted, some may want to do the minimum, but in my opinion with this kind of virus lurking, more vigilance and more intense sanitation is called for.”

Having rung the alarm bell, the plant pathologist adds some moderation.

“Panic isn’t called for, but heightened awareness is because if growers are not aware, they’re not paying attention to what’s going on. The right message here is a confidence that this virus is hardly going to threaten tomato production in the U.S., and while it may require growers to spend more on sanitation protocol, we have a number of ways we can manage the threat.”